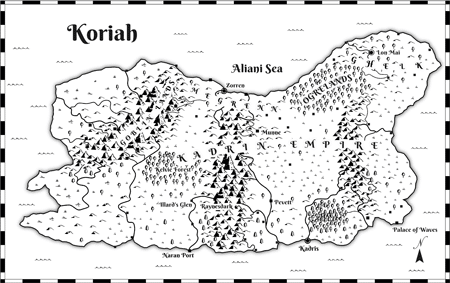

View a larger version of the map

From the Shire to Mordor, the Wall to King’s Landing and every journey in between, readers have been dragged hither and yon by epic fantasy writers for generations. Back in Homer’s day, you didn’t need a separate map to keep track of where the story took you, since maps of the real world seemed suspiciously applicable to the story. By the time hobbits and dwarves were wandering about though, maps of Ithaca and Troy were just not going to do any longer. An author is free to take it upon themselves to try to create a world entirely in the readers’ heads, but at some point, you ask too much. Far greater writers than you or I have given in. If you are going to give your readers a world so vast and sprawling, and a story to span it, then you ought to do them the not insignificant courtesy of showing them a map of the place.

Where to Begin

Well, whether you started out with one or not, at some point you’ve probably needed to sketch some sort of map just to keep things straight in your own head. There are two basic methods:

- Draw the whole map. Place every mountain, river, forest and settlement worth putting a name to all on a piece (or pieces) of paper. Ideally you’ll do it in pencil or an electronic format so that you can make revisions as you go. Hey, if your manuscript has to go through multiple rounds of editing, don’t assume your map will come through unscathed. Generally speaking though, you’ll write to the map, not the other way around. When plotting trips and making logistical plans, you already have all your major geography worked out. Offhand references to far-away places are easy to manage, since you know what all those far-away places are called already.

- Sketch-as-you-go. Using this method, you may start off knowing little more than the name of the city or village where your protagonist starts out (even if the reader or the protagonist doesn’t know, you should at least know this detail). From there, you proceed to fill in details as you go. If you need a town for a hero to flee to, pick a name, jot it down somewhere along a note that will help you place it on a map next time you update it (don’t stop your writing to update the map, batch them up and do it later). If you need a a foreign land, decide on a flavor for it, pick a name based on that, and note that too. It may become a whole separate map someday.

Mapping Ahead of Time

This can be both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, you can scale your map (miles, fathoms, days’ ride) and have all your casual references and journey times worked out believably as you write. You have only to look at your map, decide a good rate for your protagonist to travel, and tell the reader that “it is twelve days to Baron’s Marsh by horse, or you can sail around Craggy Point and be there in six”. You can also give your mind leave to focus more on plot as you write, since all the geography has already been sorted out in advance.

On the other hand, you can box yourself in by mistake. As your progress in your story, you can see that you need a new country, but it would have to exist where you’d already filled a continent with places you’ve already described. You could also need geography different that you’d mapped out. You need a river but the city you placed on a lakeside has none. You could also have found a place where it would be very useful to have snow covering someone’s tracks, but the setting is too tropical for anyone to believe it (well, it’s fantasy, so you can probably work something up, but for the time being lets keep this to mapping issues). With a willingness to revise and edit maps, nothing is insurmountable, but this can cause a gear-grinding halt that might force quite a bit of finagling.

Mapping as You Go

Full disclosure: this is the method I generally use. While I’ll generally sketch out some rough land masses, I conceive of a small functional area around my plot and keep the rest fluid. As I go, I keep track of cities, countries and geographical features that I mention in my manuscript. Much of the working copy of the map is kept in my head. On the infrequent occasions that I update my actual map and not just the notes, I have something of a logic puzzle that I’ve left for myself. Pevett and Kadris each lie on a river, but not the same one. Pevett is also on the way from High Pass to Kadris by horse, but does not lie along the path between Kadris and Raynesdark. Korgen must be near Kelvie Forest, but not so close as Illard’s Glen. The list goes on…

This might sound like an awful hassle, but it does have its advantages. First, as the puzzle comes together, the world takes shape just as you needed it to. A story that fits the world is putting the cake on top of the frosting (which, while still delicious, is backward and looks silly). The world needs to fit the story; let future stories in the same world conform. So long as you are world-building, remember that plot will always weight more heavily in the reader’s imagination than a map.

The other benefit of mapping as you go is that you have a whole toolbox of unused mountains, rivers, forests and cities at your disposal. They are an unlimited resource, ready to be invented as you need them. The next city over can be a bastion of religious piety, a trading hub filled with exotic merchants, a haven for pirates, or a backwater that’s fallen on hard times. All that matters is that it fits the purpose your story has for it.

The Reader’s Bill of Rights

Mapping edition

- It shall be legible – Check your map in the size that it will be read by your reader, whether the on-paper resolution for physical books or on-screen resolution for paperbacks

- It shall be consistent with the text – Check the map against the story, preferably via a read-through of the story with the map at hand. One cannot supersede the other, but you can choose either as the one you correct to.

- It should make sense for the world it portrays – There are exceptions to many of the Earth’s physical laws when it comes to fantasy, but if you don’t give a reason why within the story, try not to have rivers that run in circles or other such strangeness. Of course, with reason you might do anything, just make sure the readers aren’t scratching their heads in confusion

- It should relate to the story – It’s all well and good to create a map of a kingdom that you mention once in passing and no one ever visits in your story. Just don’t include it with the novel. Keep it for future works where it might be more relevant. (this is more common to pre-mappers)

- There is no 5th right

- It should contain more than merely what is mentioned – A corollary to the 4th right, mentioning eight cities by name does not mean a map with 8 cities on it and nothing else would be acceptable. Bits of geography ought to accompany what is strictly necessary to the text, whether it be more cities, mountain ranges, islands, rivers or whatnot. Your world must be believable. (this problem is more common if you map as you go; return and fill in the empty space)

- It should conform to the standards of its peers – This doesn’t mean you need to copy other mapping styles. It does suggest that you should look at other fantasy novels and understand from those the sort of expectations that readers have. Don’t give a Candyland map to a Chess audience.

How to Actually Do the Mapping

If you are a graphic designer, artist or an actual cartographer, you’ve probably got this end of things nailed. Look at a few maps, decide where things ought to be, and a few hours effort to put your concept into pixels and you’re done.

For the rest of us, there are tools out there to help. In an upcoming blog, I’ll go into the nuts and bolts of how. I used Campaign Cartographer 3 for the maps I included with Firehurler.

Do any on you have a personal favorite mapping tool?

Okay, I’ll bite: what happened to the 5th right? Or did you just do that to see if you could get a reaction from someone?

In my experience, once you get to the 5th one, people will just use it to avoid responsibility.

What would you have put there? (give them fingersbreadth, they take a day’s ride…)

Excellent resource. I agree with your omission of the 5th Right. I rather enjoy map-making myself from time to time.

What happened for me, for a few of my earlier stories that evolved into something later, was I just wrote them with no map in mind at all. Then afterward, made the map gung-ho detailed. The story(ies) evolved after that point, adapting to the map, some of them dramatically so.

I suspect what I did isn’t special or anything but it was sort of a happy accident since things sorta fell into place.

Whichever you set in stone first is the one that drives the other. Map it out and you write to the map. Do all the writing first and you have to make the map agree. Try to keep both up at once and you’re going to drive yourself to distraction with edits to both 🙂

Great post! It seems that both Joe Abercrombie and Patrick Rothfuss are “map as you go” guys. I think they’re both great writers, but Rothfuss’s map is utterly bare bones, and Abercrombie refuses to include a map at all (I suspect, to avoid trapping himself with inconvenient geography in later novels). Thanks for the ideas here…

Well, the “trap” works both ways. You can map yourself into a corner, or you can write yourself into an Escher-like world where you would realize it is physically impossible to exist as described. You have to be careful either way. The “safe” play is to map first and live with any geographical issues you leave yourself.